In the days of the incandescent bulb, the CEO of a major lighting fixture company used to say to audiences, “You know, light bulbs are 95% efficient,” and then, after a pause, “…at producing heat.”

Efficiency only has meaning with respect to a desired outcome. The above mentioned “efficiency” is great if you want to keep the plumbing in an unheated garage from freezing, but if you’re making lighting fixtures, it’s a big problem.

The term, however, is often used with little or no definition, causing efforts in the name of efficiency to produce harmful and sometimes disastrous outcomes. Lean “before” stories are full of examples. A production department runs a large machine nonstop, producing WIP that clutters production areas, consumes valuable storage space, and incurs depreciation costs. The justification? High utilization shortens amortization time, improving financial efficiency.

It gets much worse, of course. Hospital administrators, advised by “efficiency” experts, independently “optimize” admitting, triage, examination, and intensive care. The results look good on the financials initially, but, over time, the “externalities” – poor morale, long wait times, deteriorating quality, rising costs – emerge with a vengeance.

Such decisions are not the result of dumb or careless choices but are prescribed practices in what W. Edwards Deming referred to as the prevailing style of management. The guiding paradigm is what he called the pyramid – the org-chart shaped framework that purportedly describes how the forces in the organization combine to create its output. According to pyramid logic, if areas A, B, and C are made more efficient, this makes the entire organization more efficient.

Deming argued that the pyramid does not reflect how work gets done in an organization, and, furthermore, that this segmented approach creates conflict between the company’s objectives and people’s own selfish interests.

“If a pyramid conveys any message at all, it is that anybody should first and foremost try to satisfy his boss (get a good rating),” he wrote in The New Economics. “The customer is not in the pyramid. A pyramid, as an organization chart, thus destroys the system, if ever one was intended.”i1

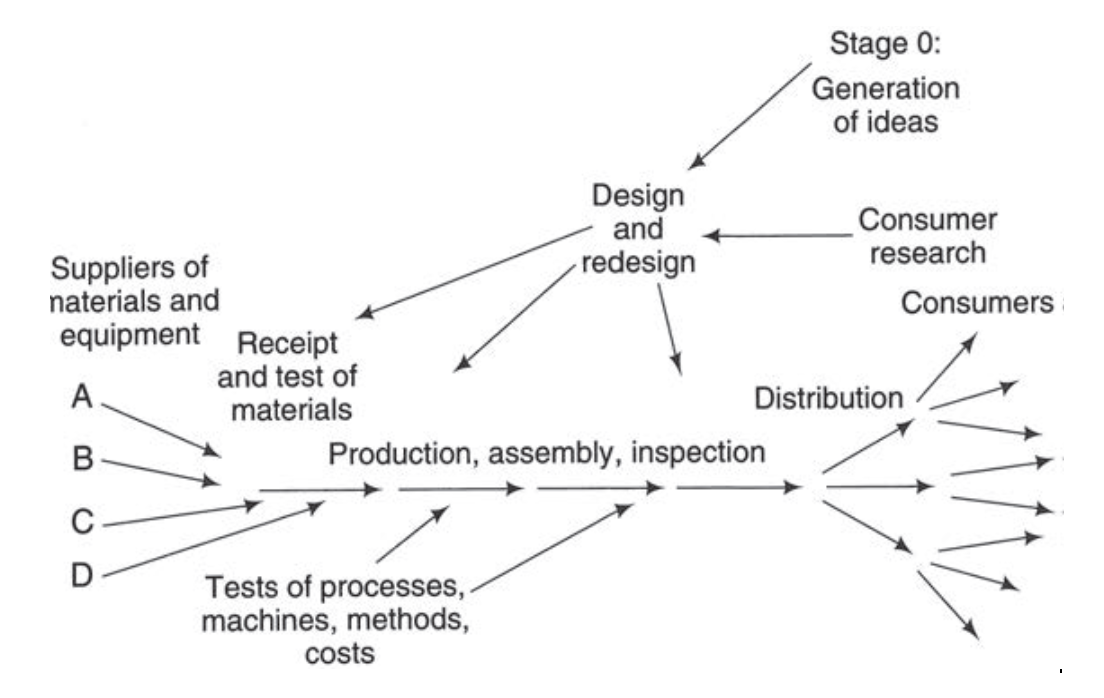

Beginning in 1950, he introduced a flow diagram as an alternative. This reflects his observation that an organization does not behave like a predictable machine that obeys org-chart logic, but as a complex adaptive system characterized by variation, non-linear relationships, and, most importantly, interdependencies between the various entities.

This changes everything. In a complex adaptive system, the efficiency of a department, a section, or any component of the organization has little bearing. What matters is the end-to-end efficiency by which the company delivers products and services of the quality that customers need at a price they are willing to pay. This requires that each component contributes, and is supported, according to the needs of the system as a whole, which must be precisely determined and thoroughly communicated by top management. Needless to say, this is a daunting challenge for leaders.

The simplified logic of the pyramid, however, is entrenched in business school curricula, hardwired into management and accounting systems, and reinforced by decades of tradition. The thinking trap is sealed off by a cognitive bias called WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is), documented by Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow.2 Here, executives who see nothing but the financials assume that there’s nothing else to see. This leaves them blind to the waste, defects, chaos, and poor morale that their efficiency initiatives might create.

It also shuts leaders out of opportunities to grow value-added with existing resources. As we see in continuous improvement scenarios, when you shorten the timeline in a value stream, quality improves and costs go down. This principle is the economic engine behind lean transformations but makes absolutely no sense to people who only see their organizations through the simplistic logic of financial efficiency.

Efficiency efforts thus place an outsized emphasis on eliminating visible costs, with headcount being a prime target. The “less people means more efficient” assumption is so widely held that when a public company announces a layoff, its share price is virtually guaranteed to go up.

“Efficiency” has therefore become somewhat of a weasel word. Software vendors claim their product will “drive efficiencies” in any organization. Outside consultants promise to find efficiencies based on best practices and industry benchmarks. Private equity companies send their financial experts into companies to assess how assets can be deployed more efficiently. All these efforts are likely to cause more harm than good.

Executives who see their people as replaceable entities on an org chart are also too easily convinced that technology, and AI in particular, can readily replace their people. On the other hand, companies that understand the interdependence of production processes and strive to develop the full capabilities of their people will, like Toyota, be in a stronger position to get a solid ROA from their technology investments and create better opportunities for their people.

The resulting competitive advantage, however, will not manifest through siloed efficiency metrics. The strengths of a well-managed system are, as Deming noted, unknowable and unmeasurable. (You can’t, for example, quantify human talent.) Accordingly, what companies should pursue is the overall efficiency by which they deploy all available resources to deliver the quality products and services that customers demand. The word for that is “productivity.”

Therefore, instead of asking “is this more efficient”, people should ask “how does this make the company more productive?” That, as former Toyota executive Kiyoshi “Nate” Furuta explained in Welcome Problems, Find Success, has been the central idea behind Toyota’s phenomenal growth.3

Productivity, however, is very difficult to measure correctly. Companies often use revenue per employee to approximate it, but such a rough estimate provides no clues about how to improve. Fortunately, thanks to accounting pioneers like Orest Fiume and Jean Cunningham, we have the tools to determine total factor productivity, the metric that reflects unit output relative to all the resources that go into its creation. The stumbling block is the belief that measuring the financial efficiency of each component of the organization will suffice.

Furuta, incidentally, didn’t talk about efficiency. Neither did Deming. But they both had a lot to say about productivity.

Parts of this article were excerpted from Productivity Reimagined by Jacob Stoller, which was published by Wiley in October 2024. For more information, please visit www.jacobstoller.com

The Lean Management Program

Build the capability to lead and sustain Lean Enterprises

At my first job as an engineer, I worked for a company that paid all of our operators on piecework, and we were obsessed with ‘efficiency.” They were measured by performance against a standard, and we prided ourselves that most of our operators were in the range of 120-140%. My job was to improve that efficiency. Meanwhile all around us was WIP and FG inventory, and our lead time was over 30 days for a product that had 10 minutes of labor.

As I advanced in the business and learned more about that JIT thing, I began to realize that we were very efficiently making the wrong product at the wrong time and had the consolation of knowing that our excess, obsolete inventory was produced at the lowest cost.

Overcoming the piecework culture was our biggest challenge in transitioning to a lean operation. To improve flexibility we reduced the number of job classes, but since our operators’ “efficiency” declined, we increased the wages, a wise decision due to the value of increased flexibility.’ To reduce WIP and lead time, we put together one piece flow cells and paid the team, rather than individual, by piecework. We could never completely overcome that “piecework” culture.

After that adventure, I did some consulting and teaching at a local tech college, and I make it a policy to ban that “E” word and shudder whenever I hear that word.